Top 5 Largest National Parks in India

Mountains Curve

31 Jul, 2025

45 mins read

566

Mountains Curve

31 Jul, 2025

45 mins read

566

India’s rich tapestry of protected areas includes some of the largest national parks in the world. The top five by area – Hemis, Desert, Gangotri, Namdapha, and Khangchendzonga – span from the arid Thar Desert to the Eastern Himalayas, each harboring unique ecosystems. These parks were established to safeguard critical habitats and species, and today they offer wildlife enthusiasts and trekkers alike an immersive experience in wilderness. In the sections below, we detail each park’s size, location, history, biodiversity, adventure opportunities, nearby attractions, and ongoing conservation efforts.

Hemis National Park

Area & Location:

Hemis National Park covers 4,400 km² of high-altitude terrain in northern Ladakh (Jammu & Kashmir). Spanning elevations from about 3,000 to over 6,000 meters, it is centered in the Hemis region of the Leh district, roughly 50 km southeast of the town of Leh. Its vast area, bounded by the Indus River and encompassing the Markha and Rumbak valleys, makes it not only India’s largest national park but one of the world’s largest high-altitude parks.

History:

Hemis was declared a national park in 1981, initially protecting the Rumbak and Markha catchments (~600 km²). In 1988 it expanded to about 3,350 km² and by 1990 reached its current 4,400 km². The park is named after the Hemis Monastery, a famous Tibetan Buddhist monastery within its bounds. Its establishment aimed chiefly to protect the endangered snow leopard and its fragile alpine ecosystem.

Flora and Fauna:

Hemis lies in the Trans-Himalayan alpine steppe ecoregion. Vegetation includes dry coniferous and willow forests in the valleys and alpine meadows and shrublands at higher elevations. Notable plants include juniper, poplar, willow, birch and fir trees, as well as various alpine flowers (e.g. Anemone, Gentiana) and rare medicinal plants.

The park’s wildlife is headlined by the snow leopard – about 200 individuals are estimated in Hemis, mostly in the Rumbak valley. These apex predators rely on prey like the Argali (Tibetan blue sheep), Bharal (Himalayan blue sheep), and the Ladakhi urial (Shapu). A small population of Asiatic ibex also lives here. Other carnivores include the Tibetan wolf, Eurasian brown bear (endangered in India), and red fox. Smaller mammals such as Himalayan marmots and weasels occur as well. Birdlife is rich, with Himalayan and Trans-Himalayan raptors like golden eagles, lammergeiers, and Himalayan griffon vultures. In the Rumbak Valley one can spot accentors, rosefinches, and snowcocks, among others. In total, 16 mammal species and over 70 bird species have been recorded in Hemis.

Trekking and Adventure:

Hemis is famous for world-class high-altitude treks. Routes such as the Markha Valley Trek and the trail from Spituk to Stok (via the Ganda La pass) traverse the park. The park also hosts mountaineering expeditions to peaks like Stok Kangri (6,153 m) and Kang Yatse (6,496 m). Hemis even draws visitors hoping to glimpse the elusive snow leopard; winter months (January-February) are best for spotting this “ghost of the mountains†against the snow. The Hemis Monastery within the park grounds holds the famous Hemis Tsechu (festival) each summer, adding cultural interest for visitors.

Nearby Attractions and Infrastructure:

The town of Leh serves as the main gateway and base for trips into Hemis. Hemis Monastery itself is a major tourist draw. The park has a network of forest rest houses and basic camps (e.g. in Rumbak, Hemis) managed by the forest department for trekkers and researchers. Facilities in Leh and the nearby Nubra and Zanskar valleys (guesthouses, logistics) support wilderness treks, although within Hemis proper the infrastructure is minimal to preserve its wild character.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges:

Hemis faces human-wildlife conflict and grazing pressure. Over 1,600 semi-nomadic pastoralists graze flocks inside the park. This leads to competition with wildlife for forage; for example, snow leopards sometimes prey on livestock when natural prey are scarce. Overgrazing by domestic animals can degrade habitat. To mitigate this, park authorities have established predator-proof livestock pens, designated no-grazing zones, and engage villagers in Project Snow Leopard (a Ladakh-wide initiative started in 2009).

Other measures include alternative livelihood schemes (e.g. homestays, handicraft sales) and eco-tourism training to reduce dependence on grazing. A Ladakh Ecotourism Project and nature-guide training help diversify income for local youth. Despite these efforts, climate change (shrinking glaciers, changing snowfall) and ever-increasing tourism also pose challenges to Hemis’s fragile ecosystem.

Initiatives:

The Jammu & Kashmir Department of Wildlife Protection oversees Hemis. Alongside Project Snow Leopard, the park benefits from national wildlife programs (Project Tiger funds are sometimes used for broad biodiversity conservation in high-altitude parks). NGO and community-led programs (e.g. Ladakh Ecological Development Group) work with villagers to conserve habitat and species. The Hemis home-stay program links tourists directly with local families, providing jobs while fostering conservation awareness. Together, these government and local initiatives aim to balance Hemis’s protection with sustainable development for its people.

Desert National Park

Area & Location:

Covering 3,162 km² in western Rajasthan, Desert National Park encompasses part of the Thar Desert ecosystem. It lies near the cities of Jaisalmer and Barmer, straddling the Jaisalmer-Barmer district border. Roughly 40 km from Jaisalmer, the park’s sand dunes extend almost to the India-Pakistan border. About 44% of its area is sand dunes, with rocky outcrops and salt flats elsewhere.

History:

Established in 1981 (gazetted in 1980), the park was created to protect the unique desert wildlife and plants of the Thar. Its core initially covered ~1,900 km² in Jaisalmer district, later expanding to its present area. It includes historic fossils – plant and animal remains up to 180 million years old – which reflect the park’s deep geological past.

Flora and Fauna:

Desert National Park supports specialized desert flora: open grasslands, sparse thorny shrubs and hardy desert grasses dominate, interspersed with fixed dunes. Some unique tree species appear (e.g. kair, peelu). A total of 168 plant species have been recorded.

Wildlife is rich in its own way. The park is known for ungulates like the chinkara (Indian gazelle) – a symbol of desert survival. Other common mammals include the Indian wolf, desert hare, and small rodents like the Indian desert jird and gerbils. Asiatic wildcats, jackals, hedgehogs, and mongoose species also roam the thorn scrub.

Reptiles flourish in the heat, including sand geckos, spiny-tailed lizards, vipers (saw-scaled, Russell’s), and others adapted to arid life.

Avifauna is notable: resident birds include sandgrouse, various larks, shrikes, partridges, and owls. The park is crucial for the Great Indian Bustard (though its numbers have dwindled nationally, occasional sighting in these lands is possible). Raptors such as tawny eagles, steppe eagles, and falcons hunt in the skies. Migratory species like the demoiselle crane and MacQueen’s bustard visit in winter. Over 260 bird species (including waterbirds in the park’s salt lakes) have been reported.

Trekking and Adventure:

Unlike forested parks, Desert NP offers desert adventure experiences. Visitors can enjoy safaris (by 4×4 vehicles or camels) across the rolling dunes, especially around the famous Sam Sand Dunes. Camping under stars, evening bonfires, and astronomy tourism are popular activities. Birdwatching drives are also organized during migration seasons. While formal trekking is not common, guided nature walks in the cooler months allow visitors to explore dune ecology. Jaisalmer’s proximity means excursions can be done as day-trips from the city.

Nearby Attractions and Infrastructure:

The medieval city of Jaisalmer (with its famous fort and haveli museums) is the main hub. Many desert camps and eco-resorts near Sam Dunes cater to tourists, blending traditional Rajasthani hospitality with desert safaris. Infrastructure is focused on tourism experiences (camel rides, cultural performances). Within the park, very limited facilities exist beyond wildlife checkposts; most visitors stay in camps at the park’s edge. Local guides and the state forest department conduct tours. The ambience here is one of wide-open solitude, with little in the way of built infrastructure inside the park.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges:

The greatest conservation concern is the Great Indian Bustard – Desert NP falls within one of the last remaining bustard habitats. Sharp declines in bustard numbers (due to habitat loss and collisions with wind turbines outside the park) led to restrictions on wind farms in Rajasthan. Other challenges include grazing by livestock, water scarcity, and illegal hunting. To tackle this, the Rajasthan government and conservation groups monitor bustard populations and work with local communities to prevent disturbances. The park is also part of the Desert National Park Protection Zone, with forest guards enforcing anti-poaching patrols.

Initiatives:

Desert NP’s management falls under the Rajasthan Forest Department. Efforts such as community awareness camps and eco-tourism development (e.g. training local villagers as guides) aim to link livelihoods to conservation. Research projects by wildlife organizations study desert ecosystem dynamics here. Wetland restoration in park salt lakes has been attempted to support birdlife. At the national level, Desert NP was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (partially in 2008 as the Thar Desert Biosphere Reserve) to integrate human activity with biodiversity conservation. Local groups have also introduced programs like gharial reintroduction in nearby Gajner Wildlife Sanctuary to maintain connected desert river ecosystems.

Gangotri National Park

Area & Location:

Spreading over about 2,390 km², Gangotri National Park lies in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand. It encompasses the headwaters of the Bhagirathi River (a main tributary of the Ganges) in the Garhwal Himalaya. The park’s elevations range from roughly 1,800 m to over 7,000 m. The sacred Gaumukh glacier (source of the Ganges) and the Gangotri shrine lie at its northern reaches. The district’s administrative center, Uttarkashi town, is the nearest city (about 100 km away).

History:

Established in 1989, Gangotri NP was carved out to protect the high-altitude Himalayan ecosystem and the pilgrimage route to Gaumukh. Its corridors connect to Govind Pashu Vihar and Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, forming a contiguous conservation landscape.

Flora and Fauna:

Gangotri’s habitats span from subtropical forests in lower valleys to alpine meadows and permanent ice fields. Lower elevations feature coniferous forests of chir pine, deodar, fir, spruce, oak, and rhododendrons. Above the treeline, alpine shrubs and meadows prevail, rich in wildflowers and grasses.

Wildlife is diverse: the park is famed for its snow leopard, which roams the alpine zones. Other large carnivores include the Himalayan black bear and brown bear, and tiger in the lower forests (occasionally wandering in). The elusive musk deer frequents forests above 3,000 m. Herding species are abundant: blue sheep (bharal), Himalayan tahr, and Indian ibex are commonly seen.

Birdlife is likewise impressive: the crest of the Himalaya brings spectacular species such as the Himalayan monal (state bird of Uttarakhand), Tibetan snowcock, khoel, and various pheasants and partridges. In all, about 15 mammal and 150 bird species have been documented in Gangotri NP. The park is also home to smaller mammals (red fox, marmot) and numerous migratory birds (snowcock, red-billed chough, etc).

Trekking and Adventure:

Gangotri NP is a trekker’s paradise. Pilgrims trek from Gangotri village (3,100 m) to Gaumukh (4,000 m), a journey passing into the park. Beyond Gaumukh lies Tapovan and Nandanvan – meadows and the base of the Chaturangi Glacier. Other famous treks start from or pass through Gangotri, such as the Kedartal (Kedar Tal) Trek and the Arwa Tal Trek, leading to pristine glacial lakes. The trail to Gomukh Tapovan offers dramatic views of Gangotri’s glaciers and peaks. These high routes involve steep passes and alpine terrain. The entire region is sacred to Hindus, so pilgrimage is also intertwined with trekking. In winter, trekking is not feasible due to heavy snowfall. Mountaineers are also drawn to nearby peaks (e.g. Shivling, Bhagirathi group) that lie at the park’s boundary.

Nearby Attractions and Infrastructure:

The temple town of Gangotri (one of the Char Dham pilgrimage sites) at the park’s entrance provides basic facilities (lodging, shops). Trekking and mountaineering companies in Uttarkashi and Gangotri supply logistics for expeditions. Within the park, a few forest rest-houses (e.g. at Bhojbasa, Nandanvan camps) accommodate trekkers. Since the park is remote and rugged, infrastructure is minimal and mainly for pilgrim and adventure tourism. The nearest motorable road ends at Gangotri; from there, foot trails penetrate the park. The larger Uttarkashi region (including hot springs, museums) serves as a support hub outside the park.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges:

Gangotri NP’s high-altitude environment faces climate change impacts: retreating glaciers (including Gaumukh) alter water flow and habitats. Human pressure comes from pilgrimage tourism (hoards of pilgrims visit Gangotri each summer) and grazing by local shepherds in lower zones. Ensuring litter control and stopping illegal tree-cutting along trails are ongoing tasks. Wildlife challenges include occasional predation by wolves (or feral dogs) on livestock, and limited resources for anti-poaching patrols in rugged terrain. To protect snow leopards, the Uttarakhand Forest Department has installed camera traps and collars, and collaborates with NGOs on community education.

Gangotri lies within the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, giving it extra protection under biosphere guidelines. The park is co-managed by the state forest department and national agencies (Ministry of Environment) under Project Snow Leopard and Project Tiger frameworks (the latter supporting habitat management broadly).

Initiatives:

Uttarakhand’s government has launched eco-tourism programs in the region, training local youth as guides and porters, and promoting homestays to benefit Himalayan communities. Conservation programs involve women’s Self Help Groups (SHGs) in garbage collection along trekking routes. The administration works with Tribal communities (Bhotia shepherds) on sustainable grazing practices. Scientific research (e.g. by Wildlife Institute of India) monitors wildlife populations. Internationally, the Gangotri landscape is part of the Indus-Sutlej alpine complexes recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage site (with Kedarnath Sanctuary) since 2005; this status helps channel funds and expertise for conservation.

Namdapha National Park

Area & Location:

Namdapha National Park covers about 1,985 km² in Arunachal Pradesh. It lies in the far south of the state (Changlang district) bordering Myanmar, near the town of Miao. Namdapha is unique for its elevation range (200–4,500 m) spanning tropical lowland forest up to alpine zones. The Noa Dihing River cuts east-west across the park, draining into the Brahmaputra basin. This park includes the steep Dapha Bum range of the Mishmi Hills and portions of the Patkai range.

History:

Namdapha was first declared a wildlife sanctuary in 1972, upgraded to a national park in 1983, and simultaneously designated a Tiger Reserve under Project Tiger. “Namdapha†comes from local Singpho words: nam = water, dapha = origin, reflecting its riverine landscape. It was established to conserve the unparalleled biodiversity of the Eastern Himalaya rainforests and meadows. Namdapha is also a Biosphere Reserve (since 1986), reflecting its global conservation importance.

Flora and Fauna:

Namdapha is a biodiversity hotspot. Its forests harbor the northernmost tropical evergreen rainforests in the world (at ~27°N). It contains over 1,000 plant species, including rare orchids (e.g. Mishmi teeta, overharvested for medicine) and endemic trees (Pinus merkusii and Abies delavayi occur only here in India). The flora spans lowland dipterocarp forests, subtropical broadleaf, temperate conifers, alpine meadows and even patches of rainforest canopy.

Namdapha’s fauna is extraordinary. Four big cats coexist here: tiger, leopard, snow leopard, and clouded leopard – the only place on Earth with all four. Other carnivores include dhole (wild dog), Malayan sun bear, Asiatic black bear, and small cats (marbled cat, golden cat, etc). Notably, the critically endangered Namdapha flying squirrel (Biswamoyopterus biswasi) is endemic to this park.

Primates are abundant: stump-tailed macaques, slow loris, Assamese macaque, capped langur, pig-tailed macaque, and the endangered hoolock gibbon (India’s only ape) are all found here. Large herbivores include Indian elephant, gaur (bison), sambar, musk deer, takin, goral, serow, wild boar, hog deer, etc.

Birdlife is equally rich (over 425 species known). The park hosts five hornbill species and rare birds of the eastern Himalaya and Indo-Burma region. For example, the endangered white-winged wood duck and rufous-necked hornbill occur here. Other notable birds include laughingthrushes, parrotbills, and the restricted-range snowy-throated babbler. The Arunachal bulbul and various eagles, pigeons, and pheasants add to the diversity. This richness has earned Namdapha comparisons to prime wildlife areas like the Amazon.

Trekking and Adventure:

Namdapha is very remote and still largely unexplored by trekkers. However, a rugged Namdapha Rainforest Trek itinerary exists, usually over 20 days, from the park entry at Deban up to high mountains in the north. Deban is a forest camp on the Noa Dihing River where visitors can fish or hike in the adjoining forest. From there, trails pass through pristine jungle, waterfalls, and eventually to the high-altitude grasslands of the Eastern Himalayas.

The trek is extremely challenging due to thick tropical jungle, leeches, and steep terrain, and is rarely done except by experienced expedition groups. Guided nature walks around Deban (in lower park) are more common. Birdwatching hides have been set up to spot pheasants and monkeys in the dense forest. Overall, adventure tourism is in its infancy, limited by accessibility.

Nearby Attractions and Infrastructure:

The closest town is Miao, which has some guesthouses; entry to the park begins near the village of Haldibari (forest checkpost). The park offers only basic forest rest houses at Deban and Firmbase (forest camps). Deban forest lodge overlooks the river and is used by park staff and trekkers; local guides and porters are arranged here. The road ends near the park boundary; beyond that movement is on foot.

The nearest broader tourist circuits involve trips into Namdapha from tourist hubs like Itanagar (capital) or Tinsukia, with chartered drives. There is virtually no urban infrastructure inside the park – the wilderness is truly intact. Tribal villages (Tangsa, Singpho) lie around the park edges and often serve as homestays for visitors.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges:

Namdapha faces threats from illegal logging, hunting, and encroachment. The lower forests have been heavily hunted in the past, reducing prey for big cats. Tribal slash-and-burn cultivation on the fringes has also impacted some areas. In recent decades the park has been insulated by its remoteness, but new roads (e.g. from Myanmar) and migration of outsiders raise concerns.

Tiger and elephant habitats are protected by the Tiger Reserve status; the project ensures a portion of central funds for anti-poaching and community incentives. Park rangers patrol the core zones regularly. A key initiative is involving local tribes: villagers from nearby forest villages are hired as watchmen and guides (linked to the park’s “Ecotourism†scheme). There are community outreach programs educating locals about wildlife laws. However, the dense terrain and political sensitivity of the border area make enforcement difficult. Diseases such as malaria and Japanese encephalitis are also monitored, since human settlement can affect both people and primates.

Initiatives:

The Arunachal Pradesh Forest Department and the National Tiger Conservation Authority jointly manage Namdapha. In 2016–17, the park was designated an Eco-Sensitive Zone, imposing buffer restrictions around its perimeter. NGOs like WWF-India and local trusts support wildlife surveys (e.g. camera-trapping all four big cats) and livelihood projects.

One notable project is the “Blue Vanda Orchid Conservationâ€: the Mishmi Teeta (blue vanda) is a rare orchid endemic to Namdapha; its overharvesting led to bans and cultivation by villagers under oversight. The park also promotes eco-tourism: for example, the Forest Department organizes nature camps at Deban and Firmbase with stays in tents, under a “Namdapha tourist permit†scheme. These government and community-led steps aim to secure Namdapha’s irreplaceable biodiversity while providing sustainable benefits to local tribes.

Khangchendzonga National Park

Area & Location:

Kanchenjunga National Park (also spelled Khangchendzonga NP) lies in northern Sikkim, covering 1,784 km². It spans the districts of Mangan and Gyalshing, around the sacred Mt. Kanchenjunga (8,586 m), the third highest peak on Earth. The park’s altitudes range from subtropical valleys (~300 m) to permanent ice-fields above 7,800 m. Chungthang and Dzongri are among the access points in the park. In 2016, it was designated India’s first “mixed†(natural and cultural) UNESCO World Heritage Site, highlighting both its diverse ecosystems and its spiritual significance to indigenous people (the Lepcha, Bhutia and Nepali communities).

History:

Established in 1977, Khangchendzonga NP was declared a national park under Sikkim’s Forest Act. Its boundaries were expanded to 2,019 km² by 1997, and an additional sanctuary was created in 2010, unifying the whole Kanchenjunga Biosphere Reserve. The park has been managed by Sikkim’s Forest & Environment Department (now Ministry of Environment) since. Its UNESCO inscription underscores collaborative conservation with local communities who revere Kanchenjunga (known as “Mayel Lyang†– “abode of the goddessâ€).

Flora and Fauna:

The park protects an altitudinal mosaic of habitats. Lower slopes hold temperate broadleaf and mixed forests of oak, maple, birch, walnut, and rhododendrons, blending into pine and fir forests in mid-elevations. Above 4,000 m lie alpine shrubs, grasses, and meadows with numerous medicinal herbs and orchids. About half of India’s bird species and a third of its flowering plant species occur within this region (including many Himalayan endemics). Rhododendron festivals in spring draw sightseers to see the colorful blooms.

Wildlife is correspondingly rich. Khangchendzonga NP is famed for its birdlife – over 550 species have been recorded, including high-altitude specialists like blood pheasant, satyr tragopan, Himalayan snowcock, Tibetan snow pigeon, Himalayan griffon, lammergeier, and black eagle. A dhole (wild dog) population surviving at up to 4,100 m is of special interest.

Mammals include snow leopard and Himalayan brown bear in the upper zones, Himalayan tahr and blue sheep on the alpine slopes, red panda and clouded leopard in the forests, and barking deer, serow and musk deer in the mid-elevations. Asiatic black bear and sun bear inhabit the temperate jungles. The park’s fauna is part of the larger Kanchenjunga Biosphere, so even elusive species like the red panda and Himalayan musk deer find refuge here.

Trekking and Adventure:

Khangchendzonga NP is a premier trekking destination. The classic Goecha La Trek approaches the southwest face of Mt. Kanchenjunga, passing through the picturesque Yumthang (Valley of Flowers) and Dzongri meadows en route to the Goecha La pass (4,940 m). This multi-day trek offers close-up panoramas of Kanchenjunga’s snowy summits. Other treks include the shorter Dzongri to Thangsing route or longer circuits through Lepcha tribal villages.

Mountain climbing (with permits) is allowed on certain Kanchenjunga peaks, but the main peak’s summit is closed to respect local religious beliefs. Seasonal hot springs (like Yumthang’s Tso Lhamo) and alpine lakes enrich the trekking experience. The park’s trek infrastructure includes forest huts at Yuksom, Dzongri, and other campsites, and camping grounds maintained by local lodges. The high mountain scenery makes Khangchendzonga National Park a magnet for hikers, nature photographers, and mountaineers.

Nearby Attractions and Infrastructure:

The historic town of Yuksom (former Sikkim capital) is the usual trailhead for treks, with rest houses and basic shops. Lachung and Lachen (valley towns to the north) serve as bases for northern park treks. The Sikkimese capital Gangtok (outside the park) provides broader tourist infrastructure (hotels, travel agencies). Cultural attractions include Rumtek Monastery and traditional villages.

Park facilities include checkposts at entry points (e.g. Barsey Rhododendron Sanctuary to the south) and the Dzongri and Goecha La camps. Road access reaches Yuksom and Pelling (southwest corner). Within the park, luxury infrastructure is minimal to protect wilderness – trekkers sleep in tents or simple huts. However, community-run eco-camps have emerged in some areas, blending adventure with sustainable tourism.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges:

Being a World Heritage Site, Kanchenjunga NP has strong legal protection. Conservation challenges include balancing sacred tourism (pilgrimages, festivals) with ecological integrity, and mitigating human-wildlife conflict. For instance, leopards occasionally descend to villages at night. Sikkim’s government strictly regulates forest use; grazing is largely banned, and local policies forbid forest felling or hunting. Climate change is altering the park’s glaciers and alpine flora.

To address this, the Sikkim Forest Department runs anti-poaching patrols year-round and monitors key species. They collaborate with the Wildlife Institute of India on biodiversity surveys. An environmental education center in Dzongri teaches visitors about the park’s ecology and cultural heritage. Waste management along trekking routes is a priority, so programs for “trekkers’ hygiene†(e.g. carry-in carry-out waste) are enforced.

Initiatives:

A key feature of Khangchendzonga’s conservation is community involvement. The Lepcha and Bhutia communities hold Kanchenjunga as sacred and participate in its stewardship. Traditional rites (e.g. annual Lepcha rituals at mountain shrines) reinforce reverence for the landscape. Sikkim’s government has promoted homestays in villages like Tingling and Dzongri, providing locals with tourism income. Women’s Self Help Groups in Yuksom and Dzongri run guesthouses and handicraft sales to support park awareness.

In 2020, a Sikkimese policy banned the use of synthetic sacks and plastic in the Kanchenjunga area. The UNESCO designation has also unlocked international aid for sustainable development (like solar electrification and improved trails) that helps alleviate pressure on forests. Joint efforts by the state forest department, UNESCO authorities, and local NGOs (including training park guides and translators) underscore the co-management model that protects Khangchendzonga’s natural and cultural legacy.

FAQs related to National Parks in India

1. Which is the largest national park in India?

Hemis National Park in Ladakh is the largest land-based national park in India, covering approximately 4,400 square kilometers. It is located in the eastern part of Ladakh and is globally recognized for harboring one of the highest densities of snow leopards. This high-altitude park is known for its rugged terrain, alpine meadows, and wide valleys, making it a hotspot for wildlife researchers, high-altitude trekkers, and nature photographers.

2. How many national parks are there in India?

As of 2025, India has a total of 106 national parks, covering around 1.35% of the country’s total geographical area. These national parks are managed by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, and they play a crucial role in protecting diverse ecosystems, endangered species, and natural landscapes. From tropical rainforests to alpine meadows, India’s national parks represent nearly every major ecological zone found on the subcontinent.

3. What is the difference between a wildlife sanctuary and a national park?

The main difference lies in protection levels and human activity regulations. In a national park, activities like grazing, hunting, or resource collection are strictly prohibited. National parks are declared under Section 35 of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, and enjoy a higher degree of protection. Wildlife sanctuaries allow some regulated human activity and are generally more flexible in their land-use rules. Both serve as critical wildlife habitats, but national parks are more tightly controlled.

4. Which is the smallest national park in India?

The South Button Island National Park in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands is India’s smallest national park, covering only 5.19 square kilometers. Despite its small size, it is biologically rich and important for marine biodiversity. The park features vibrant coral reefs, shallow lagoons, and crystal-clear waters, making it ideal for underwater photography, scuba diving, and ecological studies. It is especially important for marine conservation efforts in the Bay of Bengal.

5. What is the oldest national park in India?

India’s oldest national park is Jim Corbett National Park, established in 1936 as Hailey National Park. Located in Uttarakhand, it was renamed after the famous British-Indian hunter-turned-conservationist, Jim Corbett. The park is situated in the sub-Himalayan belt and is one of the most important areas under Project Tiger. Known for its tiger population, diverse flora, and dense Sal forests, it is a premier wildlife tourism destination in India.

6. Which national park is famous for snow leopards?

Hemis National Park in Ladakh is internationally known for having one of the highest concentrations of snow leopards in the wild. These elusive predators thrive in the park’s cold desert and alpine environment, making it a leading site for snow leopard conservation. Wildlife photographers and researchers from around the world visit Hemis during winter tracking expeditions to catch rare glimpses of this endangered big cat in its natural high-altitude habitat.

7. Are all national parks in India open throughout the year?

No, not all national parks remain open year-round. Parks located in Himalayan or monsoon-prone regions, such as Hemis, Gangotri, or Namdapha, are seasonally closed due to heavy snowfall or excessive rainfall, which affects safety and wildlife movement. Most central Indian parks like Kanha and Bandhavgarh are open from October to June, while remaining closed during monsoon months for regeneration and to avoid disturbing breeding wildlife.

8. Which national park in India has tigers?

Several national parks in India are home to Bengal tigers, and many are part of Project Tiger. Prominent ones include Jim Corbett (Uttarakhand), Kanha and Bandhavgarh (Madhya Pradesh), Ranthambore (Rajasthan), and Sundarbans (West Bengal). These parks offer some of the best chances for tiger sightings in the wild. Their ecosystems are well-managed with defined core and buffer zones to ensure the protection and breeding success of India’s national animal.

9. What is the best time to visit national parks in India?

The ideal time to visit most national parks in India is during the dry season, typically from October to April. During this period, the weather is cooler, visibility is better, and animals congregate near water sources, increasing chances of sightings. Summer months (April–June) are good for wildlife photography in dry forests like Ranthambore, while alpine parks like Hemis and Gangotri are best visited between May and September when snow recedes.

10. Are permits required to enter national parks in India?

Yes, most national parks require entry permits issued by the Forest Department or local tourism authorities. Permit requirements vary by park and may include additional fees for trekking, camping, or photography equipment. Some parks in northeastern states or border zones (e.g., Namdapha or Khangchendzonga) require Inner Line Permits (ILP) for Indian nationals and Protected Area Permits (PAP) for foreign tourists due to strategic location and biodiversity sensitivity.

11. Can we stay inside a national park in India?

Yes, several national parks allow visitors to stay inside or near the protected area in forest rest houses, eco-lodges, or government guesthouses. These accommodations are typically managed by the Forest Department and offer basic amenities. Staying inside the park provides early morning access to safari trails and better chances for wildlife sightings. However, bookings must be made in advance, and all park rules must be strictly followed.

12. Which national park has the highest biodiversity in India?

Namdapha National Park, located in Arunachal Pradesh, is widely regarded as one of the most biodiverse regions in India. It is the only park in the country where all four major big cat species (Tiger, Leopard, Snow Leopard, and Clouded Leopard) coexist. The park spans tropical, temperate, and alpine ecosystems, supporting hundreds of mammal, bird, reptile, and plant species. Its remote location also helps preserve pristine forests and rare wildlife habitats.

13. Are there any national parks in the Himalayas?

Yes, India’s Himalayan belt hosts several high-altitude national parks such as Hemis, Gangotri, Khangchendzonga, Great Himalayan, and Nanda Devi National Parks. These parks are known for snow-clad peaks, glacial lakes, rich alpine flora, and elusive fauna like snow leopards, red pandas, and Himalayan monals. They offer a combination of adventure and biodiversity, often with trekking trails that pass through remote valleys, sacred lakes, and culturally rich mountain villages.

14. Which state has the most national parks in India?

Madhya Pradesh has the highest number of national parks, with 12 officially declared parks as of 2025. The state is home to famous tiger reserves like Kanha, Bandhavgarh, Panna, and Satpura. It has earned the nickname “Tiger State of India†due to its significant tiger population. The parks here are part of the central Indian highlands and offer excellent infrastructure for safaris, wildlife tourism, and conservation awareness.

15. What is a biosphere reserve vs. a national park?

A biosphere reserve is a larger ecological area that includes a core zone (often a national park), a buffer zone, and a transition zone to balance conservation and human activity. Biosphere reserves promote sustainable development alongside biodiversity protection. In contrast, a national park is a legally designated protected area where human activity is highly restricted to conserve specific wildlife and ecosystems. Examples include Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve and Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve.

16. Which national park in India is a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

India has several national parks designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites due to their global ecological value. These include Kaziranga, Manas, and Sundarbans (all in the east) and Khangchendzonga National Park in Sikkim. Keoladeo Ghana National Park in Rajasthan is another UNESCO-listed wetland sanctuary. These parks are recognized for harboring endangered species, unique ecosystems, and cultural significance. Their inclusion enhances global cooperation for their long-term conservation.

17. Are safaris available in all national parks?

No, not all national parks offer vehicle or jeep safaris. Parks in central India such as Bandhavgarh, Kanha, Ranthambore, and Corbett are known for structured safari zones with designated routes and trained guides. In contrast, high-altitude or remote parks like Hemis, Gangotri, or Namdapha focus on trekking or walking trails, often requiring permits and local guides. Safari availability depends on terrain, wildlife sensitivity, and tourism infrastructure.

18. Can photography be done in national parks?

Yes, non-commercial photography is allowed in most national parks, though some may charge a camera fee, especially for high-end equipment. Photography helps raise awareness about wildlife and landscapes but must not disturb animals. For drone usage or commercial shoots, special permission is required from the Forest Department. Photographers should follow ethical guidelines, such as maintaining distance from wildlife, avoiding flash, and not baiting animals for shots.

19. Are there any national parks near Delhi?

Yes, several national parks are accessible within a few hours from Delhi. Jim Corbett National Park in Uttarakhand (approx. 5 hours by road), Ranthambore National Park in Rajasthan, and Keoladeo Ghana in Bharatpur are popular options. These parks are well-connected by train and road and offer opportunities for tiger sightings, bird watching, and weekend wildlife getaways. They are ideal for short trips for both adventure and photography.

20. Which animals are commonly seen in Indian national parks?

Indian national parks are home to a wide range of species. Common sightings include tigers, leopards, elephants, sloth bears, chinkara, wild boars, gaur, sambar, langurs, and various deer species. Parks also host reptiles like crocodiles and pythons and over 1300 bird species, including peacocks, hornbills, and eagles. The species seen vary by region—tropical, desert, alpine, or mangrove—and season, offering different wildlife experiences across the country.

21. Where is the Valley of Flowers National Park and what makes it special?

Valley of Flowers, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Uttarakhand, is renowned for its picturesque trekking route, vibrant alpine blooms, plunging waterfalls, and panoramic views of the snow-covered Himalayan summits. During the monsoon season, the valley bursts into color with over 600 kinds of wild flora. The journey begins at Govindghat and spans around 40 kilometers over 5 to 6 days, passing through dense woodlands, flowing streams, and timber bridges. The trail features steep ascents, especially toward Hemkund Sahib, which is surrounded by majestic peaks. Ghangaria village serves as the central trekking base for visitors.

Written By:

Mountains Curve

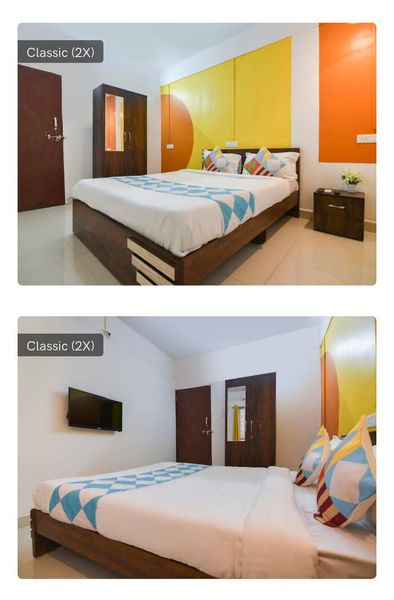

Hotels at your convenience

Now choose your stay according to your preference. From finding a place for your dream destination or a mere weekend getaway to business accommodations or brief stay, we have got you covered. Explore hotels as per your mood.